The last time, I was talking about the German adventure game Secret Files: Tunguska and how it is extremely polished but lacks value. This time, I would like to discuss another German adventure game called The Moment of Silence by the studio House of Tales.

In the Moment of Silence you control Peter Wright: a designer, who lost his wife and his kid because of his uncontrollable passion for the Photoshop liquify tool.

Comparing the two games is really fascinating because The Moment of Silence is in many ways the exact opposite of Tunguska. This has both: advantages as well as devastating consequences.

On a very basic level, the two games are very similar. Just like Tunguska, The Moment of Silence is a modern Point & Click Adventure Game. Visually they both with use pre-rendered backgrounds and superimposed real-time 3D Characters. The visual style is also comparable: neither of the game really has one. It’s all rather standard vanilla wannabe-photorealistic CGI.

However, the story in The Moment of Silence is very different. It takes place in a near future in New York. You control Peter Wright, a designer, who just recently lost his wife and child in a plane accident. Now THAT’s a character background. And this is not just cosmetic – it is actually quite essential for how the plot plays out. At the beginning of the game, Peter witnesses a SWAT team bursting into his neighbor’s apartment. His neighbor is arrested and taken away, leaving behind his wife and child. You need the help the family finding out what happened. This initial scene is not only a very simple, effective hook to get the player into a story. It also provides a clear objective. This is something which many adventure games struggle with.

The Moment of Silence begins with a bang.

But it is easy to get the beginning right. The amazing thing about The Moment of Silence is that they were able to keep it up. Now there are some spoilers in the following paragraph but I advise you to read on because let’s face it: you will probably never play the game anyway.

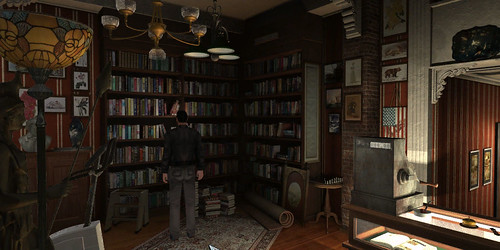

On your search for the arrested neighbor, you learn a lot about how the word in this particular future scenario works. Humanity’s knowledge is being digitized and stored on the Internet. There are actually laws forbidding people to have hard copies of books. It is considered illegal to hold back information which could be made accessible publicly. There are laws which allow the Government to have access to private information. Peter has good reasons to endorse those laws. His family was killed in a plane crash – presumably caused by a terrorists. On the other hand, his search for his neighbor reveals the problems with that kind of system. You quickly finds out that the world has turned a dystopia, comparable with 1984 or Fahrenheit 451.

Subtle Dystopia: In the world of The Moment of Silence, everybody is required to make every information publicly availible. Undigitized books and even handwriting are forbidden. The games explores the consequences.

The topic of the game is generally information privacy vs. public security. I can’t stress out enough how amazingly mature this is. The game came out just one year after U.S. troops invaded Iraq. The topic is also handled in an appropriately sophisticated way. Over the course of the game, Peter talks with a lot of people with different opinions on the subject. Many important problems and paradoxes are addressed, not only verbally but actually personified by various characters and witnessed by the player himself. This is a big deal because as I frequently point out, being able to explore a different point of view is the very essence of the unique abilities of games as a medium. In the end, this is EXACTLY what Tunguska was missing: a value beyond solving some puzzles. Something for the player to remember and consider after the game is over. A reason for the game to exist.

In my thesis about adventure games I called this particular strategy of crating value “Lebensrelevanz” which is life-relevance in German. A game is lebensrelevant if you can transfer experiences and knowledge from the game into real life and vice-versa.

Here is how Lebensrelevanz works. You play a game where you find out for example that there is this Echelon System. It is used by a couple of nations (USA, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand) to intercept and analyze transmissions like telephone calls, fax and e-mails for military intelligence. Nobody really knows what the system is capable of and used for. So you learn about it from a game, goggle it and find out that you are actually living in a city (Darmstadt) where one of the major stations of that particular system is being operated. Now THAT’s Lebensrelevanz.

It turns out I grew up right next to a Echolon base in Germany. Yikes!

In my thesis I pointed out that it is one of the unique advantages of the adventure game genre of being easily made lebensrelevant. The developers of The Moment of Silence, House of Tales seemed to have understood this. Their next game was called Overclocked and was exploring different aspects of violence.

Making a game valuable trough Lebensrelevanz is easy and effective. Actually, the plot of The Moment of Silence is not exactly a masterpiece. The ending (spoiler!) is even quite similar to Tunguska. You travel to the north pole to shut down a successor of the Echolon system, which turns out to be a crazy AI and responsible for EVERYTHING. Well, we’ve been there before but it doesn’t matter. That cheesy ending is completely dwarfed by the sophisticated discussion of the topic before. That’s is how effective Lebensrelevanz can be.

After so much praise, The Moment of Silence sadly hardly the best adventure game EVAR. Ironically it lacks EXACTLY what made Tunguska famous: polish.

It is evident everywhere. The environments looks a little less convincing than in Tunguska. They lack details, suffer from bad lightning and poor choice of colors. You frequently stumble across some questionable choices in the industrial design of objects and architecture of buildings.

An example of sloppy interior design: This is supposed to be the hallway of an apartment building. The hallway is too wide. The Display above the Elevator and the “WC” Sign are laughably huge. There are no floormats.

For the voice acting they have managed to get the German voice for Bruce Willis. In Germany every major Hollywood character has a designated voice actor who dubs this actor’s voice in EVERY movie. This way, there is consistency in how people sound in movies. So, the main character is played the German voice for Bruce Willis: Manfred Lehmann. Mr. Lehrmann is a great voice actor but, he is simply the wrong choice for this character. The voice just feels odd. Peter Wright is much younger and less masculine.

They even seem to have been unable to record everything they planned and had to implement EXTREMELY awkward workarounds. In one scene, you are supposed to get a bag from a shop. When you try to enter the shop, the door opens and somebody form inside throws the bag at you. Your character says some line about “bad manners” or something and that’s it. You can’t even enter the shop. My guess is they haven’t been able to afford the additional voice of the salesperson.

The awkward bag scene: you are supposed to fetch a bag from the owner of this shop. Instead of entering the shop and speaking to the owner, the bag is thrown at you when you open the door. You can’t enter the shop and you never hear the owner speak. No money for additional voice recording?

The puzzles also often haven’t been thought out well: in one scene you have to microwave an instant meal. You put the meal into the microwave only to realize that you are required to enter how many minutes to cook the meal. It’s written on the packaging but at this point, the meal is in the microwave and can’t be recovered for no apparent reason. You either guess, or re-load (hope you saved) or you have to use the walktrough.

I’m willing to cut the developers some slack. House of Tales is a VERY small studio, the game was done on a VERY small budget and it is 2 years older than Tunguska. However, there are two more severe issues which cannot be excused.

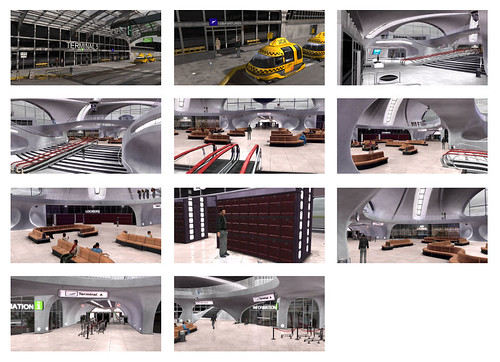

First, the developers came up with a system to show any given location from different perspectives. When you move your character trough a location, the camera sometimes switches depending on where your character is standing. It might seem like a good idea, making the game less static and more movie-like. However, there are some quite far-fetching problems. For the development, it means that you have to prepare MORE renderings of each location instead of concentrating on just one and doing it right. For a player it makes navigation and puzzle solving incredibly more difficult. There is no way of anticipating when the camera will change perspective. So the exits and the points of interest in a given location are almost impossible to identify. Sometimes the camera will switch when you walk up to the edge of the screen, sometimes it won’t. Sometimes you get a close-up when you walk up to an object, sometimes you won’t. Some camera changes are even irreversible because they would require the character to walk towards the camera which is impossible to do in a point & click interface. To add insult to injury, it is often quite difficult to re-establish your orientation after the camera has changed.

Instead of having a well-designed single screen for each location, The Moment of Silence uses a cinematic multi-angle approach. The Airport location has 11 different camera angles even though there is only one place where you can actually interact with something (the locker). Everything else is just exits and decoration. There are no indications where the exits are. At the last of the presented angles, the camera switches sides which is confusing, especially in such a monotonous environment. Also, there is a stairway which for no apparent reason can’t be used. Navigation becomes a frustrating exercise in trial and error.

The second problem is even more severe. It has to do with puzzles. They are unnecessarily frustrating because you always have access to a huge area. For the most part of the game, you can go to multiple locations in New York, each having multiple camera views. Unfortunately, the puzzles are designed sequentially so there is mostly just ONE activity the game expects you to do. If you missed a hint, simply figuring out WHERE you are supposed to be is extremely time-consuming.

Actually, this is a nice follow-up to my popular post about World Design. Back then I was describing game worlds as a collection of locations. For a more complete model you also have to consider the activities the players may perform in those locations. In many ways, locations gain meaning only trough interaction with them. That’s why a visually rich and dense environment can feel empty and austere like the cargo ship in Experience 112. In an action game the distribution of activities is simpler as they can be generated procedurally or easily changed (e.g. fighting against monsters). In an adventure games, they have to be designed manually. Hence, the distribution of activities has to be carefully thought out in advance.

In this particular case the density of activities is important. You can calculate it by dividing the number of possible activities at a given moment by the accessible locations. For adventure games low activity density (activity equals puzzle)is more frustrating. It leads to players wasting time searching for things to do, getting stuck trying to solve puzzles, which aren’t supposed to be solved at that point or aren’t puzzles at all. Conversely, in a game with high puzzle/activity density, you are rarely at the wrong place and if you get stuck, the next puzzle you can try is right behind the next corner.

There are two ways to raise activity density. You either cut down the number of availible locations or raise the number of availible activities. Tunguska did the first one and it worked great. In Tunguska you always have access to just a couple of screens so you can’t get lost and searching for clues and items is easy.

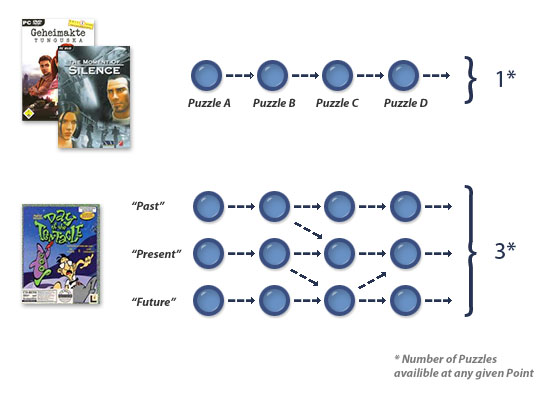

Raising the number of activities is more difficult. Remember that we are talking about the activities available AT A PARTICULAR MOMENT, not the total number of activities in the game. Many adventure games (Like The Moment of Silence and Tunguska) expect the player to perform solve the puzzles in a certain sequence one after another: Solve puzzle A, then solve puzzle B, then solve puzzle C. This is easier to design and to debug. It is also easier to bind it to a story, just like in a linear world. However, the disadvantage is that the number of availible activities is always 1, no matter how long that sequence is. In order to raise the number of activities you have to arrange the puzzles in parallel, not sequentially. I won’t go into that because this post is already too long but one particularly awesome example of a more complex activity structure is Day of the Tentacle (Maniac Mansion works too but DotT is more sexy). In that game, players have access to 3 different time periods simultaneously – the present, the past and the future. To some extent, the puzzles in the different times can be solved independent of each other and in parallel. So if you get stuck in one time period, you can always simply switch to a different one and try a different puzzle.

Sequential vs. Parallel Puzzle Structure. In Tunguska or The Moment of Silence, puzzles are arranged sequentially which is troublesome if the player has access to a large amount of locations. Day of Tentacle has at least 3 puzzles sequences running in parallel which increases the overall puzzle density.

In The Moment of Silence, a combination a sequential puzzle structure with a vast amount of locations, amplified by having multiple camera angles creates a really frustrating puzzle experience. And at this point, let me bring back the two myths of polish I mentioned in the Tunguska article. The second myth of game polish says that it is more valuable to use an already established idea and polish it really good instead of re-inventing the wheel every time. In The Moment of Silence, it would mean leaving out that cinematic camera system, cut down on some parts of the game and focus on good, polished puzzles for the remaining ones. I believe that because the its’s extraordinary topic, this would indeed result in an excellent game. Instead, we are left with yet another broken adventure.

Or are we? How does The Moment of Silence compare to Tunguska? In hindsight, I certainly favor The Moment of Silence simply because it is culturally more significant. However, this is easy for me to say when I’m not exposed to the actual game. If I had to go back and re-play one of the games, I might find myself warming up towards Tunguska.

In the end, The Moment of Silence has always one big advantage: polishing problems are mostly superficial and can be easily fixed. Fixing the Problems in Tunguska won’t be that easy. So while I probably will try Overclocked, I won’t try Tunguska 2.

This ends my pair of articles about polish in games. If you have any thoughts on this, please share them with me. I’m curious, which of the two would you prefer: cultural value or polish?

this make me think of Riven (the Myst sequel). The game was located on 1 big island with almost all places accessible and almost all puzzles available at the start of the game … which make the game very (too) difficult because they was a lot of buttons or elements to activate all over the place, which could activate something else at the other side of the island …

(in the first Myst, there was 4 or 5 different islands, with only a couple of puzzle on each)

But the great thing about Riven was that each puzzle was not here just for for the purpose of having a puzzle to resolve. Each puzzle was a device which serve a given purpose on the island, it was actually useful for the people which were living on this island. Each puzzle have a signification, and you discovered the aim of these during the game. The goal was to learn how to use the machines and/or repair them. There is too much game were you ask yourself “why would someone do that” …

about your question “cultural value or polish?” :

if by “cultural value” you mean “a real scenario”, then yes I do prefer cultural value. But I know some game without “cultural value” but with “polish” which were very enjoyable

Thanks for pointing out Riven! I haven’t thought of it. You are absolutely right, one of the biggest differences between Riven and Myst were that you have access to many locations at the Beginning of Riven – as opposed to just one island in Myst.

Did you know that they did it on purpose? The game designers figured out that many people enjoyed Myst not by solving puzzles but by simply walking around and looking at the scenery. The called them “Tourists”. Riven was specifically designed to accommodate the need of Tourist players. That’s why you can access so many locations without solving any puzzles.

I think it works well in Riven though. Riven has no inventory so you can solve a lot of the puzzles in parallel like in Day of the Tentacle. So the puzzle density is still quite high.

And yes, the fact that all the objects and machines have such a purpose and a background makes then more convincing.

By the way, “Lebensrelevanz” doesn’t equal “real scenario”. The scenario in The Moment of Silence could be considered more fantastic than the scenario in Tunguska. It plays in the future while Tunguska is contemporary. Still, the topics discussed there bear more relevance to everyday life.

To answer your question: I’d vote for polish anytime. I like your point, but I think you overestimate the importance of a good story. Adventure games are games like other computer games, so the story isn’t essential. For me, it’s more important how much fun a game is to play. Of course, the story has an influence, at least regarding Adventure games, but there are many more and more important factors. Are the puzzles fun, is the user interface smooth to control, how are the looks of the game, are the puzzles well designed, does the game set the right mood etc.

By the way, your thesis sounds _very_ interesting. Did you publish it anywhere?

Oops, I missed that last comment.

I can see your perspective on the importance of gameplay. However, I believe that if games are to be a major medium in the future, we need to develop techniques for them to provide more than mere entertainment. We need to develop techniques for them to convey meaning. This goes beyond simply “Story”, it’s also about Values and Ideas transmitted with the game.

Unfortunately, my Thesis is in German but I will probably release a digested cersion when I publish my upcoming game. Stay tuned!

I would clearly favor Tunguska, folks – because it’s much more accessible. TMoS had a good demo (albeit highlighting the game’s interface flaws) and an intriguing story, but unless you own a 19” monitor I really wouldn’t recommend it. It would have benefited greatly from Tunguska’s trumpeted “peek” function without the puzzles becoming too easy. I tried numerous times but always got turned off by the need to backtrack. And don’t talk about pixel-hunting, this game made me FEEL like a pixel!

“Overclocked” is a much better and more rewarding game, even if its main premise is clichéd. – Spoiler alert – who really believes that violent computer games turn people into evil killers? A month in a low-end job does that much more effectively, IMO, or grinding everyday pressure to conform against your will. Probably inspired by the adventure designer’s sublimated wish to take revenge on the shooter genre?