Bioshock developer Ken Levene held a talk at this year’s GDC titled “Narrative Legos”. Even though I haven’t visited GDC personally, the title stood out to me. It hints at a playful, simple, systematic and yet creative solution to the challenge of creating narrative in Videogames. It implies you could somehow break down linear narratives into modular bits that snap together to create stories with the ease of a child playing with a toy.

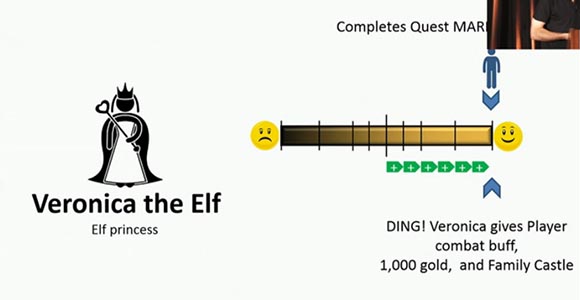

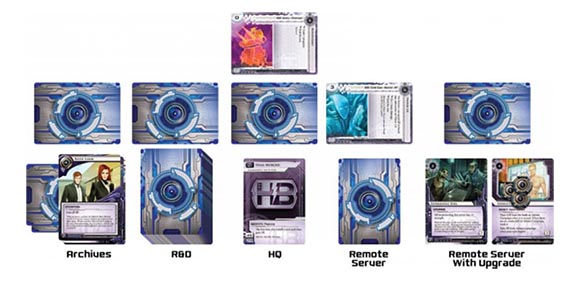

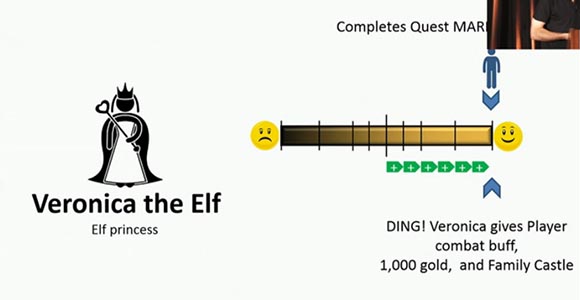

To my surprise, what Ken actually talked about is apparently an idea on how to implement NPC AI in Videogames. He proposed a system based on linear percentage bars called “Passsions”. Each NPC has multiple Passions. The player’s actions raise or lower the percentage bars depending on if the action improves or runs against a given Passion. So if an NPC hates Orcs and the player kills an Orc, that Passion bar increases. This, in turn unlocks narrative paths. Hilariously, these basically boiled down to various forms of “Combat Buffs” and we are led to believe that Ken had also smarter ideas but hasn’t mentioned them because of reasons. His ultimate goal is using this system to make a game narrative repayable and systemic like a game of Civilization. I immediately saw some fundamental issues with the presented system.

“I think we gonna need more of the “Fetch Quest”-pieces to complete this model of Ulysses.”

Living it down

The most immediate problem is that the proposed system is actually not at all different from the systems we already use in games. The karma system in Fallout 3, for example, is a global Passion percentage bar that judges player’s action on a good/evil scale. Many games implement similar systems. Mass Effect, Infamous, Black & White, you name it. Ken’s suggestion is merely to have more percentage bars instead of just one (not unlike GTA2) – to introduce more variety in the way different characters react to your actions. However, this doesn’t actually change the fundamental problems with judging the player’s actions on a linear scale.

To illustrate those problems, here is something that happened to me in Fallout 3. I decided once to actually nuke Megaton, an peaceful village. Naturally, murdering a whole community caused quite a hit for my karma rating. I lost 1000 karma points to be exact. NPCs all around me started treating me like the mass-murderer I was. So far so good. Later on, I found myself in a situation where I needed my karma rating to improve. I went to Carlos, a thirsty beggar and gave him some purified water. Each water bottle I gave him resulted in 50 karma points. Good thing I was hoarding them. Just 20 bottles set the record straight. And with that, the fact that I destroyed an entire town wasn’t a big deal anymore. The debt was paid.

“Don’t worry about that, Hank. I have a stash of water bottles to make up for it. Soon, nobody will even mention it.”

Of course, one could argue that this is just a matter of balance. Killing so many innocents should be weighted more heavily against giving away a bottle of water. Or maybe donating water bottles should yield diminishing returns. This is all true and good, but I think there is more to the problem. I claim that even if we found the “right” way to offset the moral debt of killing dozens of innocents, the fact that this is something I did should still matter in the way people interacted with me. I should not be able to live down an action like this. The fact that I can is an effect of using percentage bars. It is the effect if quantifying. We say “money does not stink”. Neither do karma points or Passion points. They don’t have a memory of how they came together. They reduce the actions of the player to a numeric value where killing a village and donating a bunch of water is the same as doing nothing. It is not a side-effect that can be tweaked out. This fundamentally the way they work.

Be My Vending Machine

Another criticism of this approach often brought up in the past is that it essentially models characters as vending machines. Characters accept favors and dish out rewards in return. It is a tragically simplistic, even sociopathic way of thinking about human relationships. It basically elevates the fetch quest to the basic building block of human interaction. How this model fails is evident in the current Friend Zone epidemic. Turns out, showering a person with favors doesn’t actually result in deeper relationships.

21st Century Character Design

Interestingly, this has been the default model for depicting romance in games. Especially Japanese interactive novels follow the same formula since ages now. Players max out a hidden “Love-meter” by paying attention to what their potential target is interested in and picking the right lines in a dialogue or making the right narrative choices. It communicates to players that in order to be successful at romance you need to to be glib, spineless, manipulative creepers. Say the right things and you’ll get in her pants. Christine Love is currently working on a game that aims at addressing and exposing those mechanisms. I’d be more interested in the kind of LEGO she builds with.

Upside-down LEGO

What applies to romantic relationships also applies to other types of relationships. But question of why the percentage bar is not a good model for human interaction is not an easy one to answer. I think a major aspect is that actions are only understood in a social context. If a stranger on the street stopped you and gave you a cake, would like him in return? Hardly. We would be probably not even willing to accept said cake. Without any further context, it is impossible for us to judge the intent of that kind of action. If anything we would be suspicious that there is something fishy about the cake. This thought experiment suggests that to some extent, Ken got it the wrong way around. It is not necessarily our actions that manipulate the status of our relationships. It is the status of our relationships that allows us to act towards each other differently.

“OMG, candy is my Passion!”

For a couple that has been together for years, expensive jewelry as a present is a way of acting out the relationship. For two teenage classmates that barely ever spoke to each other, expensive jewelry is creepy and inappropriate (even if the recipient has a “Passion” for jewelry). Buying doughnuts and coffee for your colleagues at the office is a way to live out that relationship. Buying doughnuts and coffee for the anonymous cashier at the supermarket is weird creepy and inappropriate (even if they are currently thirsty).

Everything is 0-sum

I think another way of framing the issue with Ken’s model is his tendency to think of relationships as zero-sum games. A zero-sum game is an exchange where one participant gains what the other loses. The total sum of value hasn’t changed after the exchange has been made. Ken mentions this when thinking on a global scale – his goal is to create a system where it is impossible to please everybody. Being friends with one person should make other people dislike you. But he inadvertently also implemented this system in the way he models the relationship between two people. You give me favors, I give you X (X being mostly “combat buffs”). Note that this is not how relationships work. In fact, if a partner starts treating a friendly relationship as a zero-sum game, it’s a good hint that something is going seriously wrong. We understand somebody, who marries just for money as being a manipulative asshole. Once such motivation is revealed, it can be a very good reason for divorce.

Um… does Mrs. Levine know about this?

A healthy, friendly relationship is usually something both participants draw gains from – something that creates more value where there was less before. Inviting a friend over for dinner is pleasurable and desirable for both parties. You learn about each other, you share stories, ideas, gossip. Yes, one person has to prepare the food. This investment is usually seen as insignificant compared to the value of companionship. Also, note that the size of that practical investment doesn’t necessary relate to the gains from the encounter. A more opulent meal doesn’t automatically result in a more friendly evening. It’s not something that can be maximized this way. Sometimes even the opposite can be true – a spectacularly botched-up dinner may be a bonding experience for the parties involved.

The Speed of Rumors

We already discussed how the percentage bar system doesn’t have a “memory” of the player’s actions. A related issue is that implementations of such systems often also ignore the details of information acquisition. Something that is vastly important in the way we live out relationships is careful management of appearances. We pay attention what kind of information we share with what people. Sometimes, the mere act of sharing information can actually have significant impact on a relationship. Sharing on gossip can bond two parties against another one. We are usually more sincere with people close to us, but we also feel the need to pad our relationships with “white lies”. Withholding significant information or even giving false witness is the fundamental tool for intrigue and deception. Of course, it also carries the risk of being exposed and having that knowledge being used against you. Ken showed a screenshot of Game of Thrones in his presentation. I wonder if he actually watched the series.

Oh cheer up, Sansa. Just do some fetch quests for Joffrey and he’ll love you again.

Here is a common example of how games fail to take this into account. Again, in Fallout 3, I sneak into a village. It is nighttime, nobody knows I’m here. I sneak up to an NPC and kill him in his sleep using a silent weapon. Immediately the entire village is alarmed and starts attacking me. In spite of various stealth and assassination skills, it is impossible in Fallout 3 to hide your actions or deceive characters. Every NPC in the world has instant and perfect knowledge about all your deeds. This completely eliminates all opportunity for intrigue unless certain dialogue options are specifically provided to do so.

Ken’s system also fails to reflect that. His presentation also assumes an objective truth about the player’s actions. Of course, we could easily conceive of a more complex system where the player’s actions need to be reported to NPCs before they can affect their Passion percentage bars. So after I killed some Orcs I have to actually go to the Ork-hating Elf and report to him that I killed 12 Orcs since the last time we met. Such a system exposes the opportunity for a different kind of interation. What if I just told the NPC I killed Orcs without actually killing Orcs? In most cases, there is no way for him to catch me on that. Or even better, I wouldn’t even need to lie – just having a long conversation on how I share his hatred for Orcs should be enough for him to realize that we share Passions, right? So what is this Orc-killing business even good for?

It’s not the AI that is the problem. Killing Orcs simply is a poor way to build relationships with.

3th Wheel Is The Fun Wheel

Finally, a last issue I have with Ken’s LEGO is the fact that all Passions are tracked just towards one person – the player. If another NPC kills Orcs, it won’t affect the Orc-hating Elf. Since the game is supposed to react to the player, this seems like a logical solution. But in reality, the relationships between the player and the NPCs often turn out to be the most boring ones in games.

This was an insight I had from playing the Mass Effect series. Especially in the 2nd and 3rd installment, there are some smaller romances going on between NPC team members – EDI can hook up with Joker, Tali can hook up with Garrus. To me, interacting with those relationships felt a lot more interesting than whatever Shepard had going on with his potential romance targets. Naturally, playing cupid with other people is a intriguing activity IRL. But I think there is more going on here.

She gets it!

First, manipulating a relationship you are part of within the framework of a game ALWAYS carries with it the sense of success or failure. This is especially true when it comes to romantic relationships. In games, you don’t so much romance NPCs, you game them and win them like trophies. Romancing an NPC and failing is not an attractive option. If you fail, you reload. However, when it comes to influencing the relationship between two NPCs, unsuccessful or unexpected outcomes seem much more acceptable because you are not directly affected. Urging your buddy to ask out a girl in a bar and watching him being turned down can be equally interesting as watching him succeed.

Another advantage is the symmetry of 3rd person relationships. A relationship between a player and an NPC is bound to be less detailed because the means of communication are stunted. The player can’t just talk to an NPC like they can talk to a real person, they have to use some kind of awkward interface – a multiple-choice menu in most cases. On the other side, the NPC never really understands the player, they only fire off certain pre-programmed reactions. It is a far cry for how it feels to talk to a real person. On the other hand, watching two NPCs interact with each other feels natural. Sure, the dialogue is pre-written. But it perfectly emulates how it feels like to watch to real people interact. The relationship feels more genuine because we model and perceive other people’s relationships differently from the way we model our own relationships to other people.

Finally, there is a simple technical reason for why 3rd person relationships may be more rewarding to focus on – because as the storyteller, you don’t have to show everything. Just one or two scenes between Tali and Garrus were enough for me to fill in the gaps what is going on when I wasn’t watching. At the same time, scene after scene of dialogue between Shepard and Miranda about her daddy issues have utterly failed at conveying anything close to what romance feels like.

Movies, Theater and Literature always involve the audience as a witness rather than an active participant. This may not only be a function of those mediums missing an input channel. It may be also a choice grounded in narrative affordance.

Hand Down LEGO

Multiple aspects of Ken’s narrative LEGO have been implemented for years in games. I found it quite baffling that instead of actually dealing with the issues those systems caused, Ken chose to present yet another iteration and label it as some sort of new idea. More to the point, people like Chris Crawford have been working on EXACTLY those kinds of systems, tracking multiple values across various characters to generate procedural narrative. Crawford’s Storytron was the result of experimentation with such systems for years.

Another example would be the AI engine of games like Crusader Kings 2. That engine actually exhibits a lot of the features if Ken’s proposal. It tracks opinions and personal goals of a huge number of procedurally generated NPCs. It would be worth looking into how Crusader Kings 2 gets around the fore-mentioned issues. For example, the nobility of the medieval ages is a convenient framing for a system that rewards being a scheming sociopath.

We Can Build It

I don’t know if a universal narrative LEGO is even possible. I don’t have a superior alternative ready. But since Ken’s talk is supposed to start a conversation, let us start by actually learning from existing systems instead of repeating the same mistakes. I think an improved way of modeling relationships in games should consider the following issues:

-

Remember Actions – If characters are to react to the player’s actions, they need to be able to identify and remember them. It’s the only way the player’s action can be an actual talking point. Just a percentage bar that averages away all the details doesn’t cut it.

-

Quality over Quantity – Instead of tracking linear values, a meaningful narrative model needs to find ways of expressing quality. Not every friendly relationship transitions smoothly into a romance like a linear slider suggests. We have differentiated opinions of each other. A successful system needs to be able to reflect hat.

-

Stop Trying to Make Fetch Happen – A fetch quest is a very limited way of forming and manipulating relationships. We need to come up with better verbs to improve the model.

-

Acting Instead of Winning – Modeling relationships as something to level up and win is a problematic way of portraying them. A more useful way of thinking about them may be as something players can “act out”. In this framework, the player’s actions are not means to level up relationships, they are the narrative payoff in themselves and are enabled by the relationships. Relationships shouldn’t be tied to tangible rewards. They are only meaningful if there are no ulterior motifs at play.

-

Lie to Me – A model of social character interaction must also model deception and misinformation.

-

3rd Person over 1st Person – Having the player character as a participant in a simulated relationship is a whole new can of worms. It might be easier and more effective to focus on 3rd person relationships first.