The task for this month’s Roundtable is very intriguing and quite challenging:

February’s BoRT invites you take a game design suggested by another blogger in last month’s Round Table and build upon it. You should ignore the literary source of the original design, but attempt to communicate the same themes and/or convey the same mood as the proposed game.

I really like those kinds of exercises. We did a couple of the during my design studies and it is really a great way to practice iterative design techniques. It is also quite exciting seeing other people take upon (and totally trash) your ideas like I’m quite possibly about to do now. Here’s a teaser:

For my entry, I picked up Kylie Prymus’ “Who Killed Fyodor Karamazov?”. I already talked a lot about it in the comments and in the BoRT podcast because it struck a topic I was digesting in my head for a while now. So if you want to hear my take on his initial idea, here it is:

To put my understanding of Kylie’s idea in a nut shell: it is a murder mystery where players can make decisions that will retroactively determine who the murderer was. The different choices players make would correspond to different ideologies: sensualism, intellectualism, spiritualism, etc.

The challenge in designing that game is that in order to translate those ideologies into actually gameplay, the game would need to focus on interactions with people rather than interactions with objects. After all, what ideology are you following if you put a hamster into a microwave? Interaction with characters leads often to the knee-jerk game design element of multiple choice dialogue. In my take upon Kylie’s concept, I would like to show why I think multiple choice dialogue is a BAD idea and I would like try to develop alternatives.

Interaction Density

First of all, let me explain why I think multiple choice dialogue is a bad idea. In my BoRT Digest article, I used information theory to quantify the kind of interaction players are used to from action games. In those games, there is a constant exchange of information between player and game. Players make decisions on a second to second basis, the game returns feedback at the same rate. The results are manifold. Players will get into the mythical Flow state. They will also get emotionally attached to the game, because they are essentially co-creators of whatever happens on the screen. It is basically what we value and love about games. To get down to the numbers: I estimated about 648.000 bits of information a typical NES game would process from the player per hour. Of course, players use the full bandwidth of that information stream only in rare cases like some high-end Street Fighter matches. However, this is generally the kind of exchange that is accepted as good interactivity.

And then there are multiple choice dialogues. Multiple choice dialogue has a couple of characteristics that go AGAINST what I previously established as qualities of interaction.

First, the interaction density is very low. The flow of information is heavily biased towards transmitting information to the player not receiving it. In a typical multiple choice dialogue, you will get a couple of minutes of reading and then ONE decision among maybe 5 different options. After you decide, there will be yet even more reading before you can react again. And no, pressing A to continue reading is not interaction.

This is tremendously important to realize. In my play session analysis of Hotel Dusk, there were 11 multiple choice scenes in 94 minutes of play time. They total in 25 minutes of “interactive dialogue”. If we assume that each of the 11 scenes had 6 choices to explore, even if the game would consist ENTIRELY of their version of interactive dialogue, we end up with about 80 bits of information per hour. That’s about 10 characters of text. I couldn’t even write my name with that. That’s how poor multiple choice dialogue is about receiving information from players.

(disclaimer: this is all back-of-the-napkin math. If you are a math wizard, I would appreciate proving how ignorant I am by taking into account stuff like information redundancy and entropy of human language etc…)

But there are still other problems with multiple choice. I visited Casual Connect Europe recently and the guys from PlayFirst reported something quite amazing. They did a user test of the indie point-and-click adventure Emerald City Confidential and they described how casual gamers reacted when they first encountered a multiple choice dialogue. You might think that point-and-click adventures are a good match for “casual players”. Well, when faced with their first multiple choice dialogue, most players simply froze in panic. They assumed that one of the answer as “correct” while others would lead to failure. From the kind if information they received, they couldn’t really anticipate what would happen. Even worse, after they decided, they didn’t receive a clear feedback on what effect their choice had. They were used to the transparent feedback schemes of most casual games and weren’t able to cope with the uncertainty. They simply assumed the worst and thought they messed up everything.

So basically, multiple choice dialogue will process only very little information from players and won’t give them clear feedback. It won’t create a mutual information exchange, won’t create a Flow state and won’t involve the players emotionally.

Fast-talking

I think we are ready to introduce major changes to the rusty, broken multiple choice formula. There are a couple of games that introduced small tweaks and I think we can learn from them.

First of all, one way to enhance the information density is to compress time. In the BoRTcast we mentioned very short games like The Majesty of Colors or I wish I were the Moon. They can shorten the span in which decisions are taken, shifting the balance more towards information the game receives. Short games also work well with multiple endings because they allow players to explore alternatives.

Another example of creating higher information density by compressing time is Fahrenheit aka. Indigo Prophecy (check out my review). In this game, there are traditional multiple choice dialogues but players have only a few seconds to decide what to say. To simplify decisions, the available options are not spelled out but summarized with one word. So instead of “Did you know the victim?” you will get only “Victim”. If the player fails to make a decision, the dialogue will continue but will most likely leave out on interesting topics.

Love, love is a verb, love is a doing word…

Although compressing time can help out, the problems with multiple choice dialogue a more radical rethinking. I often find the Verb / Token model quite useful for taking apart game design elements. If you rephrase a multiple choice dialogue into verbs, you will find that each choice consists of a list made up of the same verb:

“Say (insert content here)”

There are two ways of thinking about it:

You could think of each of the choices as a new, unique verb because of the “(insert content here)” part. In this case, the whole game is a collection of disposable verbs, which are used only once. This is a problem because players have trouble grasping the semantics of those verbs. Players usually learn about verbs by using them repeatedly. If verbs are used only once, it is difficult to predict the results. This fits to the observations of PlayFirst.

On the other hand, you could understand each choice as the same verb over and over again: “say”. This is no better because it would mean that multiple choice dialogues aren’t actually choices at all. Even a shallow action game has at least two verbs like “move” and “shoot”. Social interaction ought to have more depth. This actually also fits to observations of PlayFirst: players couldn’t distinguish the differences between the choices.

Radical rethinking of dialogue means structuring interaction in a different way to introduce a larger variety of verbs which are re-used throughout the game.

Hotel Dusk, which I already mentioned, has a “follow-up” verb where players can press the characters during a discussion on selected topics. But a game that pulled it off even better is Phoenix Wright (check out Yu-Chung Chen’s review of the newest installment). As far as interactive storytelling goes, it is a shining example. In Phoenix Wright, players can actually browse back and forth trough a whole statement of a witness line by line. They can then use two verbs on each of those lines: “press” and “present”. Press works pretty much like “follow-up” in Hotel Dusk but you can use it EVERYWHERE whereas the “follow-up” is only available in certain, context-relevant moments. So you can also press on parts of the statement, which may seem irrelevant. In certain missions, overusing the press verb is penalized by the game but usually, just getting no useful information is enough negative feedback.

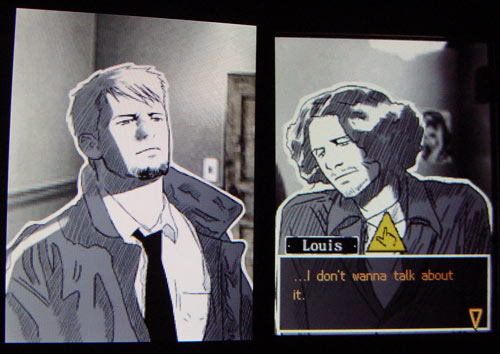

“Follow-up” verb in Hotel Dusk

The second verb, present, allows the player to present evidence that contradicts that particular part of the statement. It may seem like “say (insert content here)” but it’s not. The evidence in phoenix wright is a token – it’s things that the player can collect, “own” and manipulate. Additionally, unlike in a multiple choice dialogue, players can decide on their own when and what evidence they want to show. Also, in many cases you have to use the same evidence to debunk different statements so there is a fair amount of re-using going on.

Ha-Token!

And while we are on the subject of collectible “objects” – tokens. It is an idea used in various games. Again, Hotel Dusk has them, Phoenix Wright has them, Sam & Max has them, even Final Fantasy 2 has them. Talking to characters, players would get virtual objects they could later use in other discussions. They would be questions, ideas or topics. Hotel Dusk did both, introduce intriguing tweaks to the idea but also mess it up. In Hotel Dusk, you can collect questions which even come in three different flavors: white, yellow and red. The different colors indicate that the questions can be used in different ways I won’t go into right now. The problem with questions in Hotel Dusk is that most of the time, you use up the questions you’ve collected in the same dialogue you acquired them, making them somewhat redundant.

But dialogue tokens are a great idea to add more structure to interactive dialogue and – most importantly – to add clear FEEDBACK to the players. The very kind of feedback PlayFirst discovered players were missing.

Bringing things together

So after that long foreword, here is my concept of “Who Killed Fyodor Karamazov?”. It would be a very short game where you control a female detective and have to find the murderer. The game consists ONLY of dialogue. There is no item manipulation and no navigation. A game session should be finished under 1 hour – it doesn’t take longer in a TV series to catch the bad guy after all. So assuming you would spend 10 minutes talking to one person, you would maybe talk to 5 different characters during the game. There should be about 10 different characters in the game so you will only interview half of them during one playtrough.

The dialogue seems on-rails on first sight but players would be able to rewind a given discussion any time to a previous statement. At each particular moment, they would be use one of three different verbs, each corresponding to the three ideologies: sensualism, intellectualism, spiritualism.

- respond religiously

At any point during the discussion, players can get religious. This either results in the protagonist pulling out a fitting bible quote, blessing someone. Depending on what kind of character you are dealing with or what kind of topic is currently discussed, it will change the course of the discussion. - respond intellectually

At any point during the discussion, players can get intellectual. This would work like the press feature of Phoenix Wright or the follow-up feature of Hotel Dusk. The character would ask an inquisitive question on the subject that is currently discussed, possibly forcing a revealing statement out of the other character. - respond sensualy

At any point during the discussion, player can get sensual. Because the protagonist is female, she can use her looks to seduce a male character. Of course, using this feature would be more problematic when dealing with female characters. But generally, the verb would mean that the protagonist would try to get intimate with the other character, even if it means on a more emotional level.

But that’s not all. If players use the 3 verbs in the right moments on the right person, they gain “Charisma Points”. Charisma Points can be spend to use supermoves which – again – come in three flavors:

- religious supermove

Players can silently ask god for advice and (shocker!) actually recieve an answer. It will reveal some fact about the character they talk to which no-one can possibly know. This fact can’t be used during your investigation but will give you hints on how to proceed. - intellectual supermove

The protagonist will use his forensic profiling skills to make a silent judgment of the person he’s dealing with and reveal details which might have escaped the player. Unlike the religious facts, they can be used in the investigation but won’t be as insightful. - sensual supermove

This means actually inviting the person you are dealing with for a drink. You will get a completely new dialogue in a completely new context. The topics you will talk about will be very different. Especially as the characters get progressively drunk. You might learn something new, but you might also waste your time. But at least you will get a interesting dialogue.

After each dialogue, you can decide which character you want to interview next. During the dialogue, apart from charisma points you also collect “statements”. Between the individual scenes, the investigation will automatically reveal some hard “facts”. At any point you can decide to use the collected facts and statements to arrest a character. After the fifth or sixth dialogue, the game would have revealed enough facts to arrest a person using them alone. So even if the statements you get are rubbish, you will get a conclusion.

In order to arrest a person you need to establish do three things:

- debunk the alibi

- establish the motif

- connect the character to the scene of the crime

Each of the the three tasks can be accomplished by either using a fitting statement or fact. It will mostly be a combination of both.

As with Kylie’s original idea, depending on which verbs use, you will get different statements and maybe even different facts. So depending on how you play, you can get a different person arrested. Players should be able to get each of the 10 characters into prison. For a cool bonus twist, players also should be able to get themselves arrested.

You might even get into situation where you have the statements and facts to get different persons arrested. So the player would need to literally construct their own reality out of the facts and statements they received. Some players might ignore the facts and try to get the statements to get “that damn priest behind bars”. Others might feel like they are searching for an objective truth and only use statements that fit to the facts they got.

The challenge in actually developing that game would be to write all that dialogue. However, I think that this is much easier with a more rigid verb structure like the one presented. Also, leaving out aspects like navigation frees up resources to concentrate on the writing.

The game mechanics I presented should introduce a better information exchange. Because players can use the verbs at any point during the discussion and because the game is so short, the balance of information flow is improved. Collecting charisma points and statements adds clear feedback for players. Combining them to arrest people is yet another mechanic to receive information from players. Finally, increasing the amount of endings to 10 (or 11 counting the player itself) rationalizes having that extra information form the player in the first place. It also encourages players to try different approaches and understand that there is no “real” truth in this game – only interpretations and choices.

Ok, seriously, did you take the woman in the first image from an anti-depressant advertisement? That’s exactly what it looks like.

I know so very little of actual game design and my programming skills stopped at using PASCAL in high school “Computers” class (yes, it was officially called “Computers”) so anything I say is armchair at best. Still I appreciate what you’re trying to do here by making dialogue options more transparent. Not sure if it really replicates the sense of Flow though. But then I’m not entirely sure what it is you mean by achieving flow through dialogue choices.

I get that you don’t want the choices to be simple and obvious (which is not the same as transparent) and perhaps most importantly the player shouldn’t feel like every dialogue choice has game-changing consequences (like the casual players of ECC). Real dialogue flow should be such that no specific choice matters too much, but the sum of the choices does. But as you’ve mentioned this is just a nightmare from a design perspective.

The problem I had with Indigo Prophecy/Fahrenheit is that sometimes I would make a choice and the character would say something entirely the opposite of what I had intended. I suppose that’s what you mean by choices being not transparent enough. The question is what’s supposed to be transparent in the choice: what the character is going to say, or what reaction the interviewee is going to have?

One thing we have to realize is that in any sort of dialogue heavy game the player has to make a sharp distinction between themselves and the character (unless the player can directly type/say dialogue but that’s another thing entirely). What I like about Fahrenheit and what I’ve seen of Mass Effect (though I haven’t played it myself) is that the full dialogue choice isn’t there, so the player still gets to be a “spectator” of sorts. I want to respond angrily, so I chose to respond angrily, but then I get the joy of experiencing how that character responds angrily. This is different from, say, KOTOR where the full dialogue choices were there.

Long and muddled comment. My brain is still thinking about Street Fighter. Really great post though!

Tangential anecdote – I find it amusing that one of your graphics says fact: Shoeprints match shoes worn by Lise. If I recall you mentioned in the bortcast that you’ve not actually read The Brothers Karamazov so you wouldn’t know that Lise is wheelchair bound for the entire novel. Guess that drives home your idea of the investegator fudging the facts to reach her own conclusions!

Interesting ideas. And you are right – in a way. Leading to a good “rule of thumb”, re-think design-issues, while focus on flow on interaction – that’s good.

But on the other side I think, there is also more. Even on “poor interaction” beautiful things can be made. Who will not remember the games of Indiana Jones and Day of the Tentacle in a bliss, that are (of course not entirely!!) build around multiple-choice dialogs and made us so laugh with that charming humor. I generally are on your side, but good writing skills can also do wonder- maybe not for everyone, and maybe also nothing for “getting fast into it”. Constraints can be good.

Well, just like the concept you given. =)

Thanks for a really interesting article.

One thing that occurs to me, though, that may complicate Playfirst’s evidence: the first dialogue options in Emerald City Confidential take place in a dangerous, high-tension situation, in which it’s easy to feel that some of the options may lead directly to the protagonist’s death.

I wonder whether the casual players would have had the same reaction to a lower-stakes kind of interaction as the first dialogue sequence of the game.

I would’t diss multiple choice dialogue so quickly. Has anyone of you ever played the Fallout RPG series? Dialogue is very important and multi-choice, and choices and consequences are actually important. And your stats affect dialogue quite a lot. A must play for any gamer.

Why is everybody always excusing themselves they were no game designers? Also, programming and game design are different things.

most importantly the player shouldn’t feel like every dialogue choice has game-changing consequences (like the casual players of ECC).

In a way, but also if there are consequences, there should be immediate and clear feedback.

The problem I had with Indigo Prophecy/Fahrenheit is that sometimes I would make a choice and the character would say something entirely the opposite of what I had intended.

Yeah, I’ve experienced it also. This one problem I was referring to: because the verbs are always new and different, it’s difficult to anticipate what effects they will cause. You can lessen the impact by spelling out the beginning of the next conversation in the choice menu itself but it’s not a fix.

The separation between player and character is a good point. I’ve seen this work very well in Phoenix Wright. When using “Press” or “Push” I wasn’t always exactly clear on what the problems with the testimonies were. I often just had a vague idea that something was fishy and was glad if the main character figured it out for me.

did you take the woman in the first image from an anti-depressant advertisement?

Haha, close enough. I took it from GettyImages. They tend to look very commercially. I missed the similarity because we don’t have those advertisements in Germany. But I can imagine what you mean.

Shoeprints match shoes worn by Lise

Nice one! Cool mistake. Fits the concept perfectly.

Who will not remember the games of Indiana Jones and Day of the Tentacle in a bliss, that are (of course not entirely!!) build around multiple-choice dialogs and made us so laugh with that charming humor.

I love them just as well as you do. This kind of interaction was ok back then. It was a quantum leap over parser-based interfaces of that time. I think in times of Web 2.0, DS and iPhone we need to think about how to push things forward. Implementing different interaction doesn’t mean you have to give up humor and good writing – on the contrary. Phoenix Wright and Hotel Dusk both have some descent writing as well.

the first dialogue options in Emerald City Confidential take place in a dangerous, high-tension situation, in which it’s easy to feel that some of the options may lead directly to the protagonist’s death.

Good point! I might be wrong here but I believe the test version they had started different. But they mentioned a similar problem – the sheer nature of the first puzzle lead to (different?) complications with user testing.

Dialogue is very important and multi-choice, and choices and consequences are actually important. And your stats affect dialogue quite a lot. A must play for any gamer.

I’ve played Fallout 1 and Fallout 2, but I don’t quite understand what you think makes dialogue in Fallout different in the context of my critique. Would you mind to elaborate?

I like the direction you’re going here, Krystian! I think it’s difficult for a lot of us (including me!), to look at the mechanics beneath the game and try to innovate those in our designs, but I think that’s most important, as you’ve pointed out.

The idea that depending on the player’s investigation, any of the suspects, including the player, could be the murderer is intriguing. Even though the responses from the NPC’s are still set in stone, the player’s ability to access the responses is more intuitive.

I wonder, however, if this idea could be looked at as an even more confusing multiple-ending game. Now the player can get the number of suspects + him or herself number of endings. The dialogue system is, in a way, just obscuring the multiple choice. If you applied the mathematics to your design, wouldn’t there be an even more intimidating number of paths toward those endings? I realize your design isn’t intended to address those issues, since the short length of the game limits the density, but I’ll be interested to see how you tackle those other issues in future designs.

I love the idea and would like to see this system implemented. It will be interesting to see how Jonathan Blow tries to revamp dialogue systems, since he said he’s working on a game that attempts to do that.

@Krystian

You’re right, design and programming are two different things and it’s important to recognize that. I think for most of us the problem-solving element of game design feels a bit like program because it’s trying to use the tools at your disposal in a sometimes complicated way to produce what appears to be a smooth and easily accessed result. Like making a level in LBP. Having to learn to use the tools is the programming side, having a vision of a level is the design side, making it incorporates both in such a way that it’s not always easy to know where one ends and the other begins. But it’s important to make the distinction in general because people may think that because they have no programming skills (me) then they don’t know anything about design (but hey, I managed to italicize in html!).

Regarding the immediate and clear feedback when a dialogue choice has big consequences. For the most part I think this is appropriate and important. Just don’t forget the narrative power of occasionally having important choices seem mundane at first. We’ve all seen movies and read books where an off-hand comment ended up being the thing that sets major wheels in motion but the audience or characters don’t realize until it’s too late…

@dhalgren

With regard to the possibly confusing nature of a multiple-ending game I’m going to reference my intention in having them in my “prototype” post. I know Krystian also has some reservations about multiple-endings (hence keeping the game short which I think is good) but I sort of hope for a bit of a paradigm shift on the part of the player where they don’t try to “figure out” how to get different endings. Ideally you would play through a game like this your first time, seem to “naturally” arrive at a solution to the crime, see your ending and be satisfied that you solved it “correctly”. Perhaps you might have some questions about the designer’s intentions – why did they chose to make it a spiritual crime (if that’s the ending you go) – but if you play it again or do some research you discover that the designer didn’t directly intend that. There were multiple possibilities so the ending you received – the “moral of the story” if you will – is based just as much on your choices. In the end you see the ending that you want to see.

Hi there!

I work as a writer and designer within the game industry, and I say this only to put my remarks in context — I don’t think we “know better”, necessarily, and there should certainly always be more discussion on ways to do things.

I agree with your premise, to a point. I know that my company has done some investigation into tracking player responses to gameplay, this by an outside research company that tracks such responses via eye movement, heart rate, etc. It’s actually pretty interesting stuff. I know that we encountered some of the same results, that player’s investment in the action dropped significantly during long dialogues and picked up only when they were actually required to make a significant choice.

There is another side to that, however, and that is the emotional investment involved. My only concern with the system you propose is that it might end up feeling a little mechanical, like interacting with a spreadsheet. While pre-written dialogue trees certainly do have their weaknesses, the one advantage is that they do sound more natural and players relate to them as easily as they might a book.

Whether a book makes for good *gameplay* — perhaps that’s a different story, but not every player is looking to game their dialogue. Does that make sense? I’d be interested in seeing how such a system you propose would work, but I’m wondering if there isn’t a happy medium to be found that wouldn’t involve writing an untenable amount of dialogue.

I really like your point about information density. I had not too long ago come across the first post where you mentioned that, and it totally makes sense.

Thinking about information density has helped give me some insights about why the intro puzzles for Foldit are so boring.

Also, it’s amazing what a few concept screen shots can do for a game idea description! Seeing your mockups really makes the idea come alive and seem really cool. I can see how such a game would be compelling.

Seeing your mockups really makes the idea come alive and seem really cool. I can see how such a game would be compelling.

More, more!

Fascinating article Krystian.

I am convinced that this is the beginning of a new field in games, where dialogue will graduate from static flow charts, to something that is dynamic and can give the player unlimited options.

The premise of this article can be boiled down to the statement “redding is teh hard”.Judging the quality of interaction by the quantity of bits exchanged is flawed, as it lays on a false premise of indistinguishability between the syntax and the semantics. When you carry out an actual conversation with a person, the quantity of bits exchanged is fairly low, but the quantity of information exchanged is orders of magnitudes higher, as the words and phrases have multiple, context dependent meanings. Human brain doesn’t consider the syntax independently of the semantics, and it’s the semantics that contains the real information, and semantics of a natural language is impossible to quantify by counting bytes (characters). Implying that “Crime and Punishment” contains a few megabytes of information is hilarious.

Once we dispensed with that fallacy, we can assert that a good dialogue in a video game should approach the level of interaction between the people in the real world. In the real world conversation, you hear what the other person has to say, and, based on that and your own disposition, you form a response, that consists of one or more full sentences – you don’t think “I’m going to respond religiously” and by some magic wait for the appropriate response to form itself. Choosing between well written, natural responses that convey the intent (including at least one neutral option) is definitely preferable to choosing the keywords (”religious”, “intellectual” etc.). All choices and consequences that can be achieved by a keyword system can be achieved by dialogue trees. It is good writing that makes or breaks the dialogue trees and hiring a good writer costs orders of magnitude less than the money spent on graphic enhancements in games.

It is sufficient to provide an example of a “keyword / disposition based dialogue wheel” in Mass Effect, and compare its character interaction, that ranges between uninspired, flat and hilarious (when an unintended response happens, which is quite often) and counter it with an example of Planescape: Torment, a game with quality writing, where different dialogue options convey different personalities, where those dialogue options have an actual effect on the game world, and finally, where dialogues manage to reach the player on an emotional level.

So, let’s stop pandering to the lowest common denominator and start making games for the literate.

Wow, so many responses. I would like to thank you very much for taking your time and sharing your thoughts with us. As always, the most insightful part are the comments, not the article itself. ^_^

@dhalgren2882: You are right, I didn't really practice what I preach here. I don't really have a solution right now. I don't think there is a simple fix for those problems. The whole game must be designed with dilemma in mind. So I guess we need to try out different concepts and see what works. And I'm looking forward to Blow's new game as well!

@Kylie Prymus Good observation of small details turning out to be important later on! I haven't really taken this into account now. I think this kind of dramaturgy difficult to plan ahead in a concept stage of a game. It is generally difficult to anticipate what details players will pay attention to in a game. But ultimately, it's directing attention what good design/writing is often about.

@Emmett & janjetina: I would like to clarify something. I feel my concept has been misunderstood. It my fault because I concentrated so much on things that are different that I haven't really stressed out what remains the same. The game I envision does include dialogue. So you would read (or hear) a conversation between characters. The difference is in how you control this conversation. Instead of selecting the spelled-out answers as choices, you merely point out the manner in which the dialogue should unfold without being to specific. After you choose, you would still get a pre-written dialogue where characters act out what you’ve selected.

The other difference is that you can interact with the dialogue at any point instead of pre-defined “decision points”.

@Emmett The things you describe sound very intriguing. May I ask who you work for?

@janjetina

“redding is teh hard”

I hope the summery above cleared out some of the misunderstanding. I would have less problems agreeing to your one-sentence-breakdown if you wrote “just reading is not playing”.

When you carry out an actual conversation with a person, the quantity of bits exchanged is fairly low, but the quantity of information exchanged is orders of magnitudes higher, as the words and phrases have multiple, context dependent meanings.

Maybe. You are mixing different understandings of what “Information” is. But either was, it misses the point. In a multiple-choice dialogue the actual answers were written by the author not by the player. So their content doesn’t count as input from the player. Just as buying a book in a store is different from writing it yourself – even if you bought it because you like and understand the content.

you don’t think “I’m going to respond religiously” and by some magic wait for the appropriate response to form itself.

Actually, there are various theories how speech is constructed. The conseus seems to be that that in a conversation, the conscious focus is often on high-level strategic decision. At the same time grammar and syntax is mostly performed automatically. That’s why as a Bi-lingual with L1 attrition, I tend to start sentences I don’t have the vocabulary for anymore.

Choosing between well written, natural responses that convey the intent (including at least one neutral option) is definitely preferable to choosing the keywords (”religious”, “intellectual” etc.).

Well, it turns out it isn’t. Distilling the meaning out of a spelled-out choice adds a level of uncertainty and buden. A given sentence can be interpreted in different ways and can even change it’s meaning depending on emphasis which isn’t conveyed in written language. In the end, you mostly can only fit the beginning of the following discussion on the screen so it represents poorly what it is to come. That’s why I suggested collapsing the dialogue choice into a general intention. Not to numb down the game but to express more clearly the available choices so players can focus on the interaction instead of on interpretation.

Interesting that you’ve mentioned Mass Effect. I just started it and while I agree that the writing could be better, the way the interaction works already in the same direction as I’ve been describing here. The selection wheel is separated into 4 different regions so players can anticipate what sort of impact an answer would have without having to interpret it’s meaning. So for example selecting right/up will tend to end the discussion in a peaceful manner. Good thing too, because apart from dodgy writing the dialogue suffers from poor feedback.

So, let’s stop pandering to the lowest common denominator and start making games for the literate.

You are looking from the perspective of a player who obviously has a lot of experience with the established system. I would ask you to try to keep an open mind. Yes, bad writing will break dialogue but although good writing is necessary, it isn’t ENOUGH if we are talking about games. Games are about interaction so we must also look into different ways how to allow players to access and interact the dialogue we prepare for them. I certainly don’t think my concept is the next big thing. I’m merely trying to come up with different solutions for that lazy, stale setup as I do believe it has flaws.

You should probably look at The Witch’s Yarn. It avoids the problem Playfirst discovered.

http://www.mousechief.com

“Star Trek DS-9: Harbinger” and “Dangerous High School Girls in Trouble!” use a form of dialog trees that always moves forward. See the latter at the address above.